The Future of the Micromobility Industry

...and how companies will succeed over the next 10 years

This is the third part of a three-part analysis on micromobility. The first part explained why micromobility is so appealing as an alternative to public transportation. The second part of the analysis focused on how COVID has affected the industry and lastly, the third part focuses on the future of the industry — starting from where it is now to where it'll be in 10 years.

The following references an opinion and is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be investment advice. Seek a duly licensed professional for investment advice.

Micromobility is a young industry and yet, it's predicted to be worth between $200B - $300B by 2030. Currently, there are 127 mobility service providers that offer shared transportation methods (dockless scooters, bicycles and mopeds) across 626 cities and 53 countries. As if that didn't capture the zeitgeist of the industry, know that electric scooters (e-scooters) are the fastest growing mode of transport ever documented.

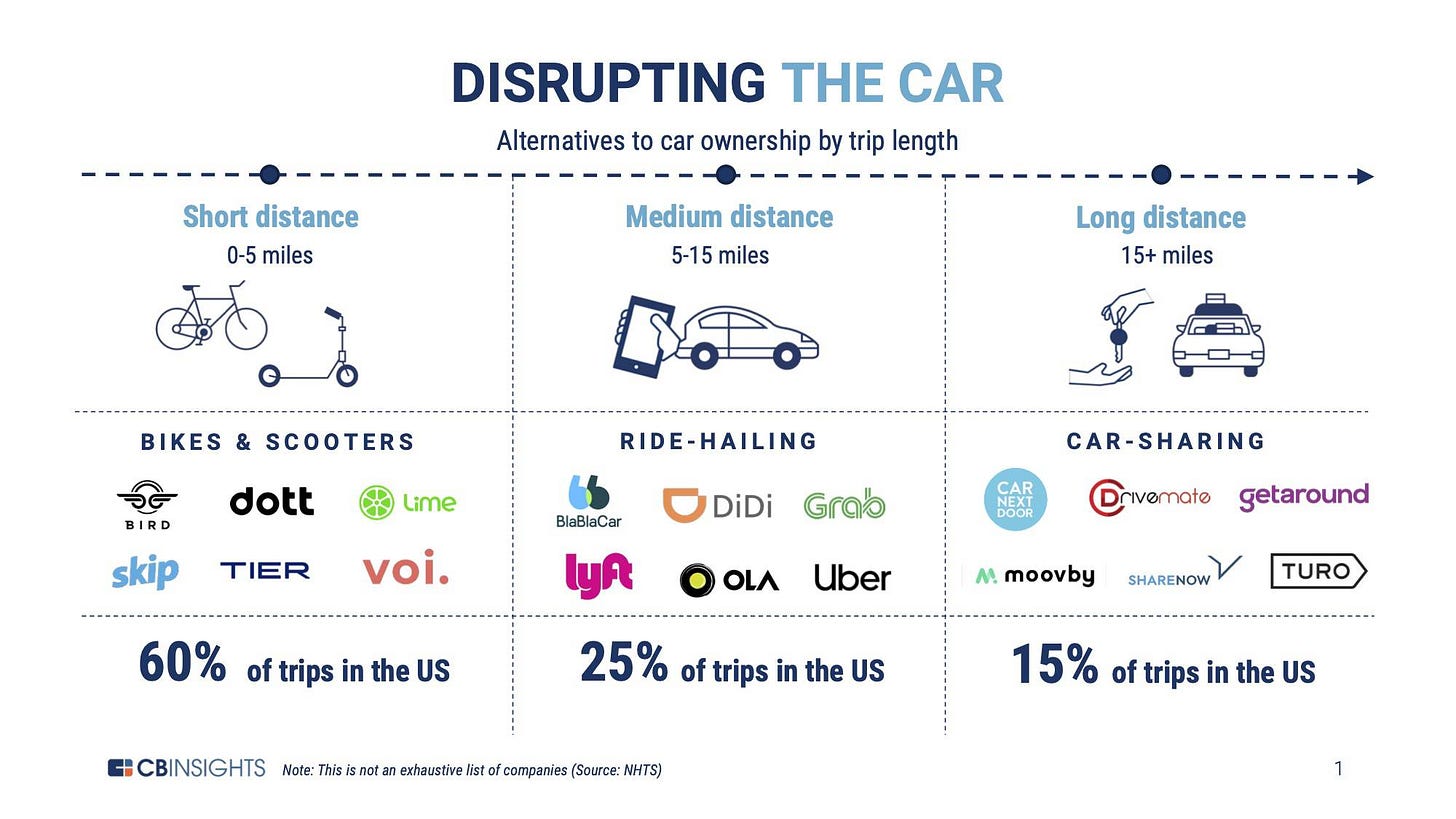

Before analyzing anything, let us define micromobility. Micromobility refers to short-distance transport, usually less than 6-miles, and has become synonymous with the growing crop of shared bikes and scooters, both human-powered and electric, docked and dockless, that have begun to remake the urban landscape.

In this analysis, we aim to understand what the industry is like today, what the challenges are, and where the industry will head over the next 10 years.

Table of Contents:

Current State

Market Analysis

The US Market

Unit Economics

Competition

Challenges

Future Opportunities & Predictions

Current State

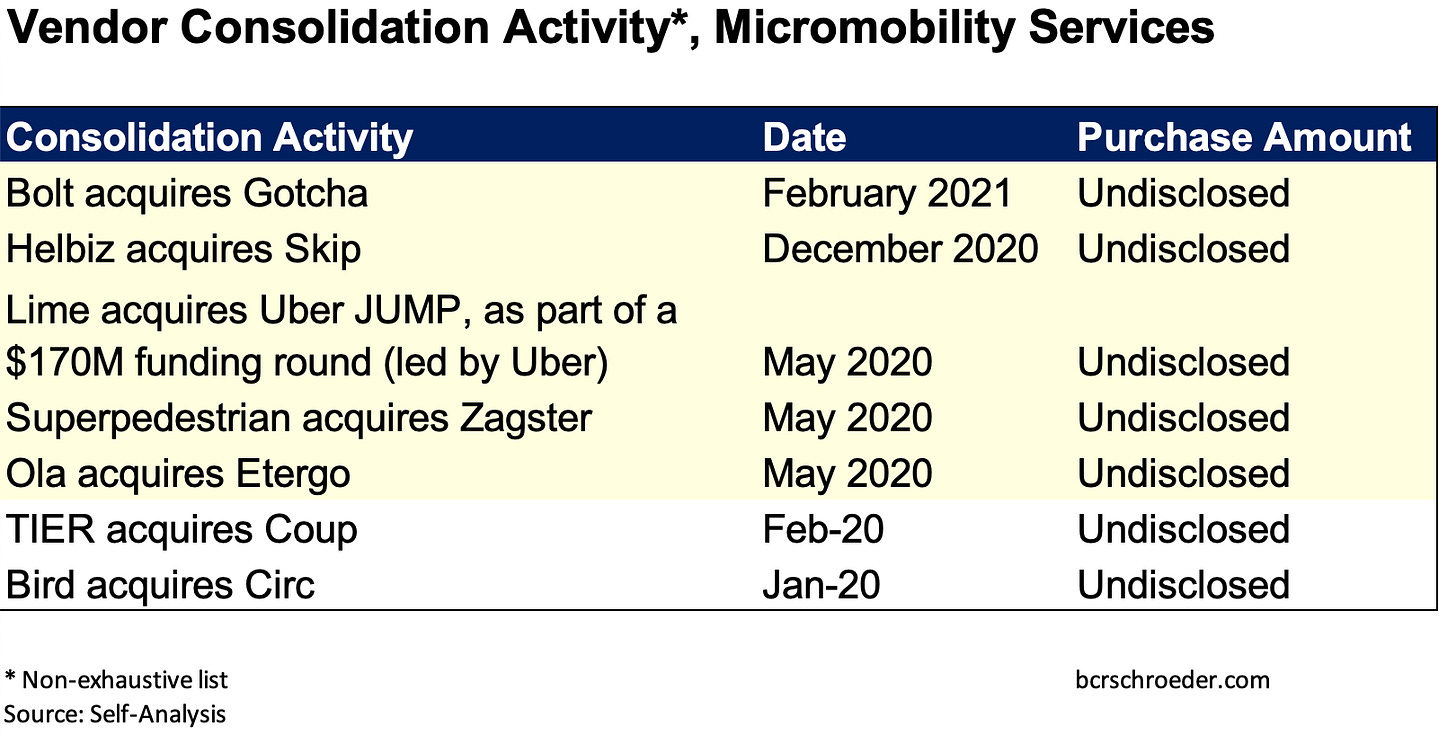

As observed in the second-part of our analysis, COVID's overall impact on the industry has been largely positive. In the short-term, the micromobility industry saw consolidation and increased adoption as cities and consumers looked for open-air, socially-distant alternatives to public transportation.

Over the long-term, our analysis showed an increased adoption of micromobility in cities while also noting the trend of individuals moving to the suburbs. Although seemingly contradictory, the reality is that moving to the suburbs will create new market opportunities for individual e-bike/e-scooter retailers but will not disrupt the growth of other micromobility platforms.

As such, the micromobility industry finds itself poised to grow in a post-pandemic world where cities begin to re-open.

To understand which companies are going to reap the rewards of this growth however, let us turn to market analysis.

Market Analysis

The US Market

The US was the first country to see dockless electric scooters in its city streets, with Bird dumping hundreds of scooters on the streets of Santa Monica in 2017. Since then, electric scooters have become the preferred method of dockless transportation and according to a 2018 survey, about 70% of Americans living in major urban areas view e-scooters positively. In fact, e-scooters are so popular in the United States that they've become the fastest growing mode of transport ever documented.

In the US, the obsession for the easy-to-use electric scooters have turned Bird and Lime, two of the first electric-scooter platforms, into industry leaders. California-based Bird achieved unicorn status ($1B+ valuation) in less than 9 months after being founded in September 2017 (the fastest company to do so) and Lime also quickly reached unicorn status.

While e-scooters startups were once among the hottest commodities money could chase, that is no longer the case. During the pandemic, Bird's valuation dropped from $2.85B to $2.3B and the company had to lay off over 400 employees (~30% of its workforce) in order to cut costs.

Similarly, Lime's latest funding round valued the company at $510M, a 79% drop in valuation compared to the April 2019 valuation of $2.4B. Like Bird, Lime had to lay off workers during the pandemic, about 13% of its workforce. Neither company is profitable.

Investorshave left the e-scooter party and are going through an e-scooter hangover.

Reason being, Bird and Lime both have simple unit-economic issues that make them fundamentally unprofitable and (in my opinion) not deserving of valuations in the $2B+ range.

Unit Economics

While e-scooters are not the only micromobility offering, they are a great microcosm for the rest of the industry. As such, let us analyze one of the most fundamental problems with e-scooters (and micromobility providers as a whole): unit economics.

Most, if not all, micromobility platforms are unprofitable. As growing startups, this is normal. Startups often require significant capital investments, high marketing costs, etc. However, most micromobility platforms (e-scooter platforms especially) are unprofitable even at a unit-economics level.

The cost of an e-scooter for Bird includes charging, maintenance/repairs, insurance, operations, payment processing fees and depreciation. However, these costs were eating away at their margins to the point where the payback period for the initial purchase of the scooter was less than the life of the scooter. That is, the company was a facing a negative return-on-investment for every scooter purchased — they economically could not be profitable.

Bird's CEO, Travis VanderZanden, tweeted in July 2019 that Bird's unit economics had just turned positive at an average of $1.27 per ride on their Bird Zero scooters.

Critics argue that Bird has stated that their Bird Zero scooters' lifespan was of 13 months, even though the scooters had only been around for 10 months at the time of posting the tweet. It could be that the scooter's life has been exaggerated to make the contribution margin positive.

Similarly, it is worth noting that the contribution margin turned positive as the summer approached. Since e-scooters are highly weather dependent, I would only believe Bird has achieved sustainable positive unit economics if it has maintained it from July 2019 through February 2020 (pre-pandemic in the US). As of writing this article, those numbers have not been published.

All the same, unit economics for e-scooter platforms have remained a challenge. While Bird claimed to have positive unit economics, Lime has made no such statement and there has been little news since.

As exemplified with e-scooter companies, a funadamental problem with the industry is making the unit-economics work and reaching profitability. Without tremendous scale and/or R&D (read: acquisitions), profitability seems unlikely.

Competition

Competition in the growing industry is fierce. In direct competition to Lime and Bird, Uber acquired bike-share startup Jump in April of 2018. Similarly, Lyft partnered with Citi Bike (NYC bike-share program) to allow the docked bikes to be rented through the Lyft app. Beyond e-scooters and bikes, there are also dockless mopeds available from Scoot and Revel.

The two big companies competing in the space are Uber and Lyft, who both hope to become a "one-stop shop" in their own regards. Uber wants to become your go-to app for, well, everything. The company acquired a majority stake in Cornershop, a grocery delivery app. It also acquired Drizly, an alcohol-delivery app and along with Uber Eats, its restaurant-food delivery app, Uber can delivery just about anything to you. Uber seems to pivoting away from transporting people to transporting goods.

Lyft on the other hand, seems to be doubling down on transporting people. With the introduction of real-time public transportation information, the company is projecting itself as the one-stop shop for all things mobility. The idea being that whenever you want to go somewhere, you open the Lyft app. In New York City for example, Lyft will show you the route, time and price for ride-hailing, Citi Bikes, car rental and the subway/bus.

There are, of course, a number of smaller startups hoping to corner their own segment of the market. For example, Revel is a dockless electric moped sharing startup founded in 2018 that is "electrifying urban mobility". Not without controversy (more on that later), the company has expanded all throughout NYC and Washington D.C. The company has recently expanded to offer an all-Tesla ride-hailing service, a monthly e-bike subscription and electric-car charging hubs.

All in all, the micromobility industry is a crowded but potentially highly-profitable industry. Before it can reach the predicted $200B-$300B market size however, it has a lot of challenges to overcome.

Challenges

Several factors continue to plague the industry as it attempts to segment itself as a serious transportation alternative.

For one, just like the beginning of the ride-hailing companies, micromobility platforms have run into a series of regulatory issues. Electric scooter companies were banned from San Francisco after the companies dumped the scooters without permissions nor permits. Similarly, Revel had to temporarily suspend its moped sharing service after 3 deaths occurred in NYC. Whether e-scooter, e-moped or other, regulatory issues will continue to plague micromobility platforms and the high-growth numbers they so deeply desire.

The longevity of the bikes, scooters and mopeds also pose a challenge to micromobility platforms. Both Bird and Lime stated that their electric scooters tend to last one to two months before having to be replaced — if even that. A dataset released by Bird found that the average life spawn of a scooter was just 28.8 days. Similarly, Revel mopeds have been a favorite target of scavengers looking to sell batteries or other parts. As such, micromobility platforms must deal with longevity issues and the stealing of scooters, moped, bikes or their component parts.

Lastly, another challenge facing companies is weather. Electric scooters and mopeds are both highly-weather dependent. In cities across California, who rarely see a day of rain, this may not be a problem. In Seattle however, where on averageit rains 42% of the time, consumer usage may be limited by weather.

That being said, none of the aforementioned challenges are insurmountable. Regulation will slowly be put in place, longevity issues will be resolved through product iterations, and companies will ultimately have to be selective about the cities in which they expand. With that in mind, let us turn to the industry's future opportunities.

Future Opportunities & Predictions

Future opportunities within the micromobility industry lie in the global post-COVID bounce-back and in consolidation.

Using the post-COVID bounce-back effectively is crucial. Companies within the industry are in a sink-or-swim environment and retaining the customers that tried their service during COVID or boosting their marketing efforts as cities re-open are the solutions. Why? For one, because as people start going out and traveling again, others will see individuals riding these services. Whether it be Revel, Bird, Lime, Citi Bike, Capital Bike or any-other, social proof will convince reluctant individuals to try it — and adopt it.

Additionally, I believe that brands who helped individuals successfully navigate COVID have a deep emotional (trauma) bond with their consumers. In the highly commoditized micromobility industry, having a brand advantage can be significant.

The second source of future opportunity is in consolidation.

Micromobility services have high upfront costs, high maintenance costs, and benefit tremendously from economies of scale. Less choice is easier for consumers but most importantly, being a larger company gives you more bargaining power. Because regulation/city governments are the ultimate roadblock for companies in this industry, having more bargaining power is essential for growth. The bigger and better-established a company is, the less likely a city is to not accept their proposal. I believe the industry only has space for around 3 large micromobility service providers, like ride-hailing today, which makes more consolidation a certainty.

While there may be regional offerings, such as NYC's Citi Bike or Washington DC's Capital Bike, these offerings will be integrated into some larger provider — like Citi Bike can be payed for via Lyft. Smaller, geographically-focused and/or one-vehicle-only micromobility services (Bird, Lift, etc.) will be acquired by larger players looking to access new markets or expand their offerings.

I also predict that the 3 "big players", nationwide one-stop-apps for all things mobility, will focus on a particular market segment. This phenomenon can already be seen with Lyft, Uber, and Revel, with Lyft positioning itself as an app exclusively for "human mobility", Uber increasingly positioning itself as the app for "commodity mobility" (food, groceries, alcohol, etc.) and Revel, albeit a small company, positioning itself as an electric-only offering (e-mopeds, e-charging stations and all-Tesla ride-hailing fleet).

Over the next 5-10 years, I expect that independent players will be pushed aside or acquired into another's solution and that ultimately, only about 3 large nationwide micromobility providers will prevail. Regional providers will still exist, however they will all be integrated into the offerings of some larger provider.

If you enjoy my work, why not buy me a coffee ? It helps me write, stay motivated, and shows that you truly found my article insightful.